“They build dams and kill people.” These words, spoken by a witness when the murderers of environmental defender Berta Cáceres were brought to trial in Honduras, describe Desarrollos Energéticos SA (DESA), the company whose dam project Berta opposed. DESA was created in May 2009 solely to build the Agua Zarca hydroelectric scheme, using the waters of the Gualcarque River, regarded as sacred by the Lenca communities who live on its banks. As Nina Lakhani makes clear in her book Who Killed Berta Cáceres?, DESA was one of many companies to benefit from the 2009 coup d’état in Honduras, when the left-leaning President Manuel Zelaya was deposed and replaced by a sequence of corrupt administrations. The president of DESA and its head of security were both US-trained former Honduran military officers, schooled in counterinsurgency. By 2010, despite having no track record of building dams, DESA had already obtained the permits it needed to produce and sell electricity, and by 2011, with no local consultation, it had received its environmental licence.

Much of Honduras’s corruption derives from the drug trade, leading last year to being labelled a narco-state in which (according to the prosecution in a US court case against the current president’s brother) drug traffickers “infiltrated the Honduran government and they controlled it.” But equally devastating for many rural communities has been the government’s embrace of extractivism – an economic model that sees the future of countries like Honduras (and the future wealth of their elites) in the plundering and export of its natural resources. Mega-projects that produce energy, mine gold and other minerals, or convert forests to palm-oil plantations, are being opposed by activists who, like Cáceres, have been killed or are under threat. Lakhani quotes a high-ranking judge she spoke to, sacked for denouncing the 2009 coup, as saying that Zelaya was deposed precisely because he stood in the way of this economic model and the roll-out of extractive industries that it required.

The coup “unleashed a tsunami of environmentally destructive ‘development’ projects as the new regime set about seizing resource-rich territories.” After the post-coup elections, the then president Porfirio Lobo declared Honduras open for business, aiming to “relaunch Honduras as the most attractive investment destination in Latin America.” Over eight years, almost 200 mining projects were approved. Cáceres received a leaked list of rivers, including the Gualcarque, that were to be secretly “sold off” to produce hydroelectricity. The Honduran congress went on to approve dozens of such projects without any consultation with affected communities. Berta’s campaign to defend the rivers began on July 26, 2011 when she led the Lenca-based COPINH (“Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras”) in a march on the presidential palace. As a result, Lobo met Cáceres and promised there would be consultations before projects began – a promise he never kept.

Lakhani’s book gives us an insight into the personal history that brought Berta Cáceres to this point. She came from a family of political activists. As a teenager she read books on Marxism and the Cuban revolution. But Honduras is unlike its three neighbouring countries where there were strong revolutionary movements in the 1970s and 1980s. The US had already been granted free rein in Honduras in exchange for “dollars, training in torture-based interrogation methods, and silence.” It was a country the US could count on, having used it in the 1980s as the base for its “Contra” war against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Its elite governing class, dominated by rich families from Eastern Europe and the Middle East, was also unusual. One, the Atala Zablah family, became the financial backers of the dam; others, such as Miguel Facussé Barjum, with his palm oil plantations in the Bajo Aguán, backed other exploitative projects.

At the age of only 18, looking for political inspiration and action, Berta left Honduras and went with her future husband Salvador Zúñiga to neighbouring El Salvador. She joined the FMLN guerrilla movement and spent months fighting against the US-supported right-wing government. Zúñiga describes her as having been “strong and fearless” even when the unit they were in came under attack. But in an important sense, her strong political convictions were tempered by the fighting: she resolved that “whatever we did in Honduras, it would be without guns.”

Inspired also by the Zapatista struggle in Mexico and by Guatemala’s feminist leader Rigoberta Menchú, Berta and Salvador created COPINH in 1993 to demand indigenous rights for the Lenca people, organising their first march on the capital Tegucigalpa in 1994. From this point Berta began to learn of the experiences of Honduras’s other indigenous groups, especially the Garífuna on its northern coast, and saw how they fitted within a pattern repeated across Latin America. As Lakhani says, “she always understood local struggles in political and geopolitical terms.” By 2001 she was speaking at international conferences challenging the neo-liberal economic model, basing her arguments on the exploitation experienced by the Honduran communities she now knew well. She warned of an impending “death sentence” for the Lenca people, tragically foreseeing the fate of herself and other Lenca leaders. Mexican activist Gustavo Castro, later to be targeted alongside her, said “Berta helped make Honduras visible. Until then, its social movement, political struggles and resistance were largely unknown to the rest of the region.”

In Río Blanco, where the Lenca community voted 401 to 7 against the dam, COPINH’s struggle continued. By 2013, the community seemed close to winning, at the cost of activists being killed or injured by soldiers guarding the construction. They had blocked the access road to the site for a whole year and the Chinese engineering firm had given up its contract. The World Bank allegedly pulled its funding, although Lakhani shows that its money later went back into the project via a bank owned by the Atala Faraj family. In April 2015 Berta was awarded the Goldman Prize for her “grassroots campaign that successfully pressured the world’s largest dam builder to pull out of the Agua Zarca Dam.”

Then in July 2015, DESA decided to go ahead by itself. Peaceful protests were met by violent repression and bulldozers demolished settlements. Threats against the leaders, and Berta in particular, increased. Protective measures granted to her by the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights were never properly implemented. On February 20 2016, a peaceful march was stopped and 100 protesters were detained by DESA guards. On February 25, 50 families had to watch the demolition of their houses in the community of La Jarcia.

The horrific events on the night of Wednesday March 2 are retold by Nina Lakhani. Armed men burst through the back door of Berta’s house and shot her. They also injured Gustavo Castro, who was visiting Berta; he waited until the men had left, found her, and she died in his arms. Early the following morning, police and army officers arrived, dealing aggressively with the family and community members who were waiting to speak to them. Attempted robbery, a jilted lover and rivalry within COPINH were all considered as motives for the crime. Eventually, investigators turned their attention to those who had threatened to kill her in the preceding months. By the first anniversary of Berta’s death the stuttering investigation had led to eight arrests, but the people who ordered the murder were still enjoying impunity. Some of the accused were connected to the military, which was not surprising since Lakhani later revealed in a report for The Guardian that she had uncovered a military hit list with Berta’s name on it. In the book she reports that the ex-soldier who told her about it is still in hiding: he had seen not only the list but also one of the secret torture centers maintained by the military.

Nina Lakhani is a brave reporter. She had to be. Since the coup in Honduras, 83 journalists have been killed; 21 were thrown in prison during the period when Lakhani was writing her book. She poses the question “would we ever know who killed Berta Cáceres?” and sets out to answer it. Despite her diligent and often risky investigation, she can only give a partial answer. Those arrested and since convicted almost certainly include the hitmen who carried out the murder, but it is far from the clear that the intellectual authors of the crime have been caught. In 2017 Lakhani interviewed or attempted to interview all eight of those imprisoned and awaiting trial, casting a sometimes-sympathetic light on their likely involvement and why they took part.

It took almost two years before one of the crime’s likely instigators, David Castillo, the president of DESA, was arrested. Lakhani heads back to prison to interview him, too, and finds that Castillo disquietingly thinks she is the reason he’s in prison. “There is no way I am ever sitting down to talk to her,” he says to the guard. Nevertheless they talk, with Castillo both denying his involvement in the murder and accusing Lakhani of implicating him. Afterwards she takes “a big breath” and writes down what he’s said.

In September 2018, the murder case finally went to trial, and Lakhani is at court to hear it, but the hearing is suspended. On the same day she starts to receive threats, reported in London’s Press Gazette and duly receiving international attention. Not surprisingly she sees this as an attempt to intimidate her into not covering the trial. Nevertheless, when it reopens on October 25, she is there.

The trial reveals a weird mix of diligent police work and careful forensic evidence, together with the investigation’s obvious gaps. Not the least of these was the absence of Gustavo Castro, the only witness, whose return to Honduras was obstructed by the attorney general’s office. Castillo, though by then charged with masterminding the murder, was not part of the trial. Most of the evidence was not made public or even revealed to the accused. The Cáceres family’s lawyers were denied a part in the trial.

“The who did what, why and how was missing,” says Lakhani, “until we got the phone evidence which was the game changer.” The phone evidence benefitted from an expert witness who explained in detail how it implicated the accused. She revealed that an earlier plan to carry out the murder in February was postponed. She showed the positions of the accused on the night in the following month when Berta was killed. She also made clear that members of the Atala family were involved.

When the verdict was delivered on November 29 2018, seven of the eight accused were found guilty, but it wasn’t until December 2019 that they were given long sentences. That’s where Nina Lakhani’s story ends. By then Honduras had endured a fraudulent election, its president’s brother had been found guilty of drug running in the US, and tens of thousands of Hondurans were heading north in migrant caravans. David Castillo hasn’t yet been brought to trial, and last year was accused by the School of Americas Watch of involvement in a wider range of crimes. Lakhani revealed in The Guardian that he owns a luxury home in Texas. He’s in preventative detention, but according to COPINH enjoys “VIP” conditions and may well be released because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Two of those already imprisoned may also be released. Daniel Atala Midence, accused by COPINH of being a key intellectual author of the crime as DESA’s chief financial officer, has never been indicted.

The Agua Zarca dam project has not been officially cancelled although DESA’s phone number and email address are no longer in service. Other environmentally disastrous projects continue to face opposition by COPINH and its sister organisations representing different Honduran communities. And a full answer to the question “Who Killed Berta Cáceres?” is still awaited.

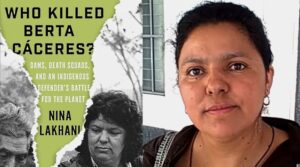

Who Killed Berta Cáceres?: Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet, by Nina Lakhani. Verso, 2020. 336 pp.

Original post: Council on Hemispheric Affairs and also on Counterpunch

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on