Street march in Masaya, July 2022

July 19th is a day of celebration in Nicaragua: the anniversary of the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship. But the international media will have it penciled in their diaries for another reason: it’s yet another opportunity to pour scorn on Nicaragua’s Sandinista government. We’ll hear again about how the government “clamps down on dissent,” about its “political prisoners,” its recent “pantomime election,” its “damaging crackdown on civil society” and much more. All of these accusations have been answered but the media will continue to shut out any evidence that conflicts with the consensus narrative about Nicaragua, that its president, Daniel Ortega, has “crushed the Nicaraguan dream.”

Mainstream media tells its own story

Since the violent, U.S.-directed coup attempt in 2018, in which more than 200 people died, it has been very difficult to find objective analysis of the political situation in Nicaragua in mainstream media, much less any examination of the revolution’s achievements. In disregarding what is actually happening in the country, the media is ignoring and excluding the lived experience of ordinary Nicaraguans, as if their daily lives are irrelevant to any judgment about the direction the country is taking. Most notably, instead of recognizing that 75% of Nicaraguan voters supported the government in last November’s election, in which two-thirds of the electorate participated, the result is seen as “a turn toward an openly dictatorial model.” This judgment is backed by confected claims of electoral fraud from “secret poll watchers,” which ignore COHA’s strong evidence that no fraud took place.

Streets show the political reality

In the run-up to the anniversary of the revolution on July 19th, Sandinista supporters have been filling the streets of every main city with celebratory marches. In Masaya, where I live, I took part in a procession with around 3,000 people and discovered afterwards that three other marches took place at the same time in different parts of Masaya, with even more people participating in each of those. People have much to celebrate: the city was one of those most damaged by the violent coup attempt in Nicaragua four years ago, but has since lived in peace.

During the attempted coup, for three months the city of Masaya was controlled by armed thugs (still regularly described in the media as “peaceful” protesters). Five police officers and several civilians were killed. The town hall, the main secondary school, the old tourist market and other government buildings were set on fire. Houses of Sandinista supporters were ransacked. Shops were looted and the economic life of one of Nicaragua’s most important commercial centers was suspended. My own doctor’s house went up in flames and a friend who was defending the municipal depot when it was ransacked was kidnapped, tortured and later had to have an arm amputated as a result.

So one strong motive for the marches is to reaffirm most people’s wishes that this should never happen again: 43 years ago a revolutionary war ended in the Sandinistas’ triumph over Somoza, but this was quickly followed by the U.S.-sponsored Contra attacks that cost thousands more lives. For anyone over 35, the violence in 2018 was a sickening reminder of these wars. Since then, not the least of the government’s achievements is that Nicaragua has returned to having the lowest homicide level in Central America, and people want it to stay that way.

Progress under Sandinistas is not recognized internationally

But this is far from the government’s only success since it returned to power in 2007. It inherited a country broken by 17 years of neoliberal governments by and for the rich (after the Sandinistas lost power in the 1990 election). Nothing worked during those years: there were daily power cuts, roads were in shocking disrepair, some 100,000s of children didn’t go to school and poverty was rampant. When the Sandinistas regained the presidency in 2007, and helped by the alliance with Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela and a boom in commodities prices, the government began a massive investment program. For the second poorest country in Latin America, the transformation was remarkable.

Take the practical issues that affect everyone. Power cuts stopped because the new government quickly built small new power stations and then encouraged massive investment in renewable energy. Electricity coverage now reaches over 99% of households, up from just 50% in 2006, with three-quarters now generated from renewables. Piped water reaches 93% of city dwellers compared with 65% in 2007. In 2007, Nicaragua had 2,044 km of paved roads, mostly in bad condition. Now it has 4,300 km, half of them built in the last 15 years, giving it the best roads in Central America.

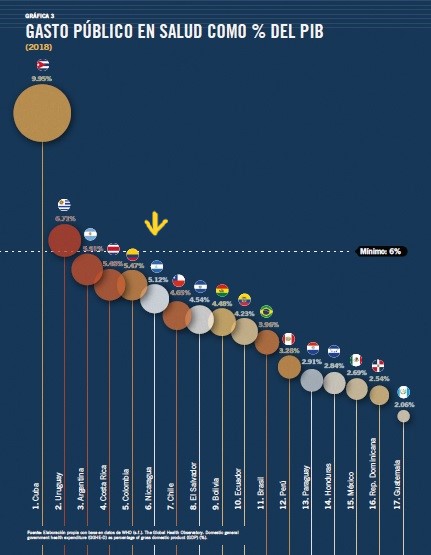

Its remarkable advances in health care were evidenced by how Nicaragua handled the COVID-19 pandemic, with (according to the World Health Organization) a level of excess mortality far lower than that of many wealthier countries in Latin America, including neighboring Costa Rica. It now has one of the world’s highest levels of completed vaccinations against the virus (83%), exceeding levels in the U.S. and many European countries. There has been massive investment in the public health service: Nicaragua has built 23 new hospitals in the past 15 years and now has more hospital beds (1.8 per 1,000 population) than richer countries such as Mexico (1.5) and Colombia (1.7). The country has one of the highest regional levels of public health spending, relative to GDP (“PIB” in Spanish – see chart), and its service is completely free.

Nicaragua is 6th out of 17 Latin American countries in public health investment

Source: Centre for Economic and Social Rights, Desigual y Letal, p.58.

Look at education. School attendance increased from 79% to 91% when charges imposed by previous governments were abolished; now pupils get help with uniforms and books and all receive free school lunches. Free education now extends into adulthood, so out of a population of 6.6 million, some 1.7 million are currently receiving public education in some form. Under neoliberal governments illiteracy rose to 22% of the population, and now it’s down to 4-6%.

Strides in gender parity: another victory

Nicaraguan women have been integral to the revolution. More than half of ministerial posts are held by women, an achievement for which Nicaragua is ranked seventh in the world in gender equality in 2022. Only two countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have a smaller gender pay gap than Nicaragua. More than a third of police officers are female and there are special women’s centers in 119 police stations. Maternal health has been significantly improved, with maternal mortality falling from 92.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2006, to 31.6 in 2021, a reduction of 66%. This is partly due to the 180 casas maternas where women stay close to a hospital or health center for the weeks before giving birth. The state also provides family planning free of charge in all health centers, including tubal ligations for women who do not wish to have more children. It is also true, of course, that abortion is illegal, but (unlike in other Latin American countries) no woman or doctor has ever been prosecuted under this law.

At the moment, people’s biggest concern is the state of the economy and the cost-of-living crisis. Nicaragua has advantages here, too: it is more than 80% self-sufficient in basic foodstuffs and prices have been controlled because the government is capping the cost of fuel (both for vehicles and for cooking). Nicaragua’s economy grew by more than 10% in 2021, returning to 2019, pre-pandemic economic levels, although growth was still not sufficient for the country to recover from the economic damage caused by the 2018 coup attempt. Government debt (forecast to be 46% of GDP in 2022) is lower than its neighbors, especially that of Costa Rica (70%), where poverty now extends to 30% of the population. However, Nicaragua and Costa Rica are economically interdependent, and the latter’s economic problems are a large part of the explanation for the growth in migration by Nicaraguans to the United States.

Daniel Ortega enjoys high approval ratings

These are only a few of the factors that underlie people’s support for Daniel Ortega’s government. And this support continues: according to polling by CID Gallup, in early January President Ortega was more popular than the then presidents of Honduras, Costa Rica or Guatemala. M&R Consultants, in a more recent poll, found that Ortega has a 70% approval rating and ranks second among Latin American presidents. This was obvious when huge numbers of Nicaraguans celebrated November’s election result and it is still obvious as they go out onto the streets during “victorious July”.

At a meeting with Central American foreign ministers in June 2021, U.S. Secretary of State Blinken urged governments “to work to improve the lives of people in our countries in real, concrete ways.” Blinken deliberately ignores the ample proof that Daniel Ortega’s government is not only doing that but has been more successful in this respect than any other Central American government. Yet the more that the international media parrot Washington’s criticisms of Daniel Ortega, the more that people here will reaffirm their support for his government.

Original post: Council on Hemispheric Affairs, LA Progressive, Resumen Latinoamericano, Popular Resistance, Nicanotes, United Anti-War Coaliton (UNAC) and Tortilla con Sal. En español aqui y aqui.

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on

A great piece; Thanks John.

Alan Wallace

Thanks Alan, and apologies again for the delay in posting!