US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo launched another attack on Nicaragua’s Sandinista government last month, accusing President Daniel Ortega of being a “dictator” who is “doubling down on repression and refusing to honor the democratic aspirations of the Nicaraguan people.” The State Department openly supports what it calls “a return to democracy in Nicaragua”, saying that “the people of Nicaragua rose up peacefully to call for change.”

Pompeo’s accusations came in a month in which Nicaragua’s National Assembly made three new legislative proposals, the most important of which aims to limit this kind of foreign interference in Nicaraguan politics. Predictably, a range of international bodies echoed Pompeo’s criticisms. Human Rights Watch said that Ortega is “tightening his authoritarian grip.” Amnesty International claimed that Daniel Ortega plans “to silence those who criticize government policies, inform the population and defend human rights.” Reporters without Frontiers, the Committee to Protect Journalists and PEN International all sprang to the defense of press freedom. Fox News called this response “an international outcry” and Reuters said that the government plans to “silence” the opposition.

So what is the Nicaraguan government really doing? Are its action unusual compared with other countries? Is there a need for the new law?

Three bills have been introduced in the Nicaraguan legislature, its National Assembly, and are currently being debated:

- One is to regulate “foreign agents.” New regulations would require those receiving foreign money for “political purposes” to register with the Ministry of the Interior and explain what the money is used for. Similar regulations exist in the US.

- The second is to tackle cybercrime and penalize hacking; it would prohibit publication or dissemination of false or distorted information, “likely to spread anxiety, anguish or fear.”

- The third is to enable sentences of life imprisonment for the worst violent crimes (as applies in the US, except of course in states which use capital punishment).

This article concentrates on the first of these new laws, as it is the most controversial, but we will briefly explain the other two.

Fake news and fake deaths

The second proposal arises from the desire to curb the massive “fake news” campaigns that began in 2018, with announcements of deaths that never took place. It also aims to prevent social media posts that call for attacks on people or publicize violent crimes such as torture by filming them and posting them. Most recently, there have been campaigns aimed at convincing people with COVID-19 symptoms not to go to hospital, and these undoubtedly did deter some people from getting help and made it more difficult for the government to control the pandemic. Whether such fake news can be successfully restricted is, of course, a debatable point, but the government’s legislative changes are explicable even if their likely effectiveness might be uncertain.

The third proposal also has origins in the violence of 2018, when opposition mobs kidnapped and tortured police officers, government officials and Sandinista supporters. But its immediate justification is the recent horrific rape and murder of two young sisters in the rural town of Mulukukú, by a criminal who had taken part in an opposition attack on the local police station in 2018, in which three police officers were killed. He had been captured in 2018, found guilty and imprisoned, but was included by the opposition in their list of so-called “political prisoners.” He was then released as part of the general amnesty of June 2019, instituted by the government under tremendous international pressure. Nicaragua’s legal system has no death sentences and limits prison terms to a maximum of 30 years; the law would enable judges to imprison for life those found guilty of the worst crimes. The Washington Post interpreted the law as threatening life sentences for government opponents, which is far from the truth.

The law to regulate “foreign agents”

The proposal causing the biggest outcry is the far more straightforward “foreign agents” bill. It would require all organizations, agencies or individuals, who work with, receive funds from or respond to organizations that are owned or controlled directly or indirectly by foreign governments or entities, to register as foreign agents with the Ministry of the Interior. Anonymous donations are prohibited. Donations must be received through any supervised financial institution and must explain amounts, destinations, uses and purposes of the money donated. Foreign agents must refrain from intervening in domestic political issues, which means that any organization, movement, political party, coalition or political alliance or association that receives foreign funding could not be involved in Nicaraguan politics. Wálmaro Gutiérrez, Chairman of the National Assembly Committee responsible for scrutiny of the new bill, offered this synopsis: “Only we Nicaraguans can resolve in Nicaragua the issues that concern us. In summary, that is what the foreign agents law says.”

Despite the protests from Amnesty International and others, and the Financial Times calling the new measure “Putin Law,” the world is full of precedents to control foreign involvement in political activities. For example, of the countries within the European Union, 13 have very strict laws relating to foreign political funding and only four have no restrictions at all. In Sweden, receiving money from a foreign power or someone acting on behalf of a foreign power is a criminal offence if the aim is to influence public opinion on matters relating to governance of the country or national security. The US Library of Congress has further examples from many different countries illustrating the wide range of different powers used.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the widest and strictest legal provisions apply in the United States. They prevent not just foreign governments, but foreign entities of any kind, from involvement in US political activity. Particular restrictions are imposed by the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA), which requires a wide range of bodies that receive foreign funding to register as “foreign agents,” with severe penalties for non-compliance. A recent case involving a non-governmental organization (NGO) showed that the law requires registration for activities that are so broad in scope that most people would not consider them to be “political” at all (the NGO deals with environmental projects). The lawyers reporting this case advise NGOs that “they may be required to register under FARA, even if funding they receive from foreign governments is only part of the organization’s financial resources and the proposed work aligns with the non-profit’s existing mission.”

Political parties are not the only target of the new law

Why is the new law not limited to political parties, like the similar restrictions in (for example) some European countries? The reason is that Nicaragua has a small number of very politicized third-sector organizations: NGOs, “human rights” bodies and media organizations that receive foreign funding for political purposes (it also, of course, has thousands of NGOs that receive foreign money for legitimate purposes, such as poverty relief). An example occurred as this article was being written.

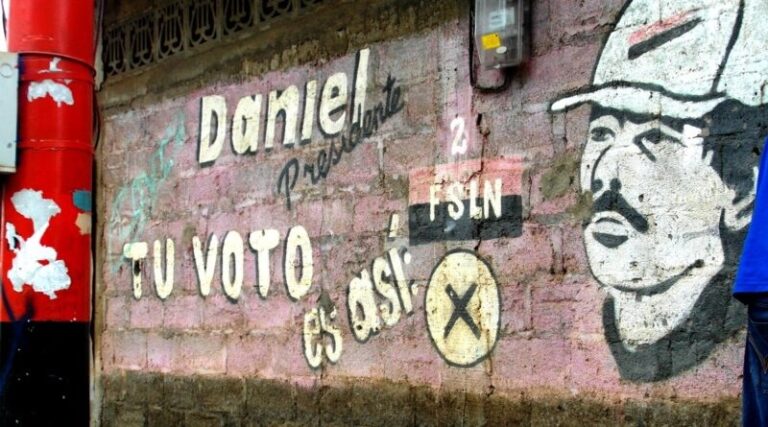

Photos courtesy of Tortilla con Sal

Posters have appeared on the streets of the capital, Managua, with messages such as “For Nicaragua, I’m able to change” or “Nicaragua matters to me” (see first photo). Allegedly, the poster campaign, run by Nicaragua’s Bishops’ Conference, began after Catholic bishops who support opposition groups met with US embassy officials, who agreed to pay the costs of the campaign. Whether or not this is true, the purpose of the posters is clear. While to someone unfamiliar with Nicaraguan politics the messages may appear harmless or even anodyne, to local people the words and colors make it obvious that they are publicity supporting the loose coalition of groups and parties who aim to oust Daniel Ortega in next year’s election. Indeed, as can be seen from the second photo, memes parodying the originals have already begun to appear in social media.

The posters may also form part of the latest US operation, known as “RAIN” (“Responsive Resistance in Nicaragua”), recently reported by COHA, through which the US plans to interfere in Nicaragua’s 2021 elections via USAID. But the US government’s practice of using third-sector bodies to influence Nicaraguan politics has a long history. It dates back at least to the time of the “Contra” war in the 1980s, a massive illegal operation funded and directed by the US that left tens of thousands of Nicaraguans dead and for which the International Court of Justice ordered the United States to pay compensation to Nicaragua. One of the legacies of that proxy war is that the Reagan administration created a Nicaraguan “human rights” NGO, the Nicaragua Association for Human Rights (ANPDH), to whitewash evidence of atrocities by the US’s own Contra forces. That NGO still operates today and continues to answer to the US by attributing opposition atrocities to the Nicaraguan government. (A short history of the ANPDH and similar bodies and their links to the US has appeared in The Grayzone.)

US funding of Nicaraguan “civil society” organizations resumed soon after the Sandinistas regained power in the election of 2006. The blog Behind Back Doors published documents revealing that one US agency, USAID, began a strategy in 2010 to influence the Nicaraguan elections over the following decade, allocating $76 million to projects with political parties, NGOs and opposition media. Some of this funding was directed via the National Democratic Institute (NDI), specifically to strengthen six opposition political parties (even though equivalent work by a foreign government in the US would of course be illegal). Among the many NGOs to receive funding was one, the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation (named after the president who succeeded Daniel Ortega in 1990, and run by the most prominent of the opposition political families), which received over $6 million that it then directed to opposition media outlets (including ones owned by the Chamorros themselves). The aim of the program was to “undermin[e] the image of the Nicaraguan government at the beginning of the electoral process of 2016.” In the last two years, USAID audits, the most recent from August 2020, show that a further $2 million has been allocated under the same program. As Nicaraguan commentator William Grigsby explained in his radio program Sin Fronteras, one result of US funding is that more than 25 TV and radio stations, syndicated TV and radio programs, newspapers and websites freely produce anti-Sandinista rhetoric.

It is noteworthy that, when the Financial Times (FT) reported critical responses to the planned new laws, they included ones from the Chamorro family and from the body that represents the “independent” press, without pointing out their financial stake in continued US funding. The FT also reported criticism by the US National Endowment for Democracy (NED), without pointing out that it is one of the US state organs that is driving the problem which the Nicaraguan government seeks to tackle.

Why is the funding of local NGOs being challenged now?

Sandinista governments have been in power over much of the period since the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, during most of which time opposition NGOs have been able to operate within a normal framework of regulation of a kind that operates in most (if not all) countries of the world. The need for tighter controls became apparent two years ago. April 2018 saw the start of what the US still calls “peaceful public protests” but which in fact were very violent, with several NGOs, “human rights” bodies and opposition media actively supporting the violence or creating fake news as to who was responsible for it.

There is plentiful evidence of this violence, of course. The most recent, detailed reports come from central Nicaragua, in a series of harrowing interviews with victims recently conducted by Stephen Sefton. The NGOs and media bodies being targeted by the new law either denied that this violence was occurring or attempted to blame it on the police or Sandinistas. Many of the same NGOs and media were also involved in undermining the government’s strategy for dealing with the COVID-19 crisis, as COHA has already reported. Their campaigns caused suffering and loss of life among people deterred from going to public hospitals as a result of fake news about clandestine burials, deaths of prominent public figures or a collapse of the hospital system, often illustrated with photos or videos from other countries which they claimed were from Nicaragua.

As the 2021 election year approaches, the scale of the newly started “RAIN” project suggests to many observers that it has a dual purpose: supporting the opposition’s election campaign, but also laying the groundwork to delegitimize the elections in the event of another Sandinista victory. The US Embassy and the State Department will continue to assert that the Nicaraguan government is running “a sustained campaign of violence and repression,” contrary to Nicaraguans’ “right to free assembly and expression,” regardless of whether the new law is implemented. It is clearer than ever that some NGOs and similar bodies are an integral part of this offensive.

This abusive extension of the role of NGOs is, of course, a trend across Latin America and indeed the rest of the world. An article in the magazine of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent, asks whether the “N” in “NGOs” has gone missing? It warns that, as “a significant proportion of their income comes from official government channels, NGOs will resemble more an instrument of foreign policy and less a force for change and advocacy.” In particular, it might be argued, those NGOs that allow themselves to be enlisted by the US government in its beneficial-sounding programs to “promote democracy” in different countries are in practice signing up to a very different purpose. There is now a range of US government bodies and private US institutions who work together to exercise soft power on behalf of the US regime change agenda in various countries through the medium of local NGOs.

William Robinson, who worked in Nicaragua in the 1980s, argues that the real objective is not only regime change:

“‘Democracy promotion’ programmes seek to cultivate these transnationally oriented elites who are favourably disposed to open up their countries to free trade and transnational corporate investment. They also seek to isolate those counter-elites who are not amenable to the transnational project and also to contain the masses from becoming politicized and mobilized on their own, independent of or in opposition to the transnational elite project by incorporating them ‘consensually’ into the political order these programmes seek to establish.”

In the context of Nicaragua, this suggests that democracy promotion through local NGOs, “human rights” bodies and media organizations is not merely about seeking Daniel Ortega’s defeat at the polls, but achieving a paradigm shift away from governments that prioritize the needs of the poor to put power back into the hands of the elite who answer to transnational interests, as in other countries of Central America which have not experienced Nicaragua’s revolutionary change.

Nicaragua is only exercising the same rights as those used by the United States

Chuck Kaufman of the Alliance for Global Justice maintains that Nicaragua has the right to know about and protect itself from foreign funding of its domestic opposition. He goes on to argue that “a country is not required to cooperate in its own overthrow by a foreign power.” This does of course have echoes of the United States’ own actions in rejecting foreign interference in its domestic politics. William Grigsby of Radio La Primerísima argues that the US is hypocritical in criticizing Nicaragua’s restrictions on foreign influence on local media outlets when the US government has itself put restrictions on the US media operations of companies based in China, Venezuela, Russia, and Qatar. Former libertarian Congressman Ron Paul is reported to have said, “It is particularly Orwellian to call US manipulation of foreign elections ‘promoting democracy.’ How would we Americans feel if for example the Chinese arrived with millions of dollars to support certain candidates deemed friendly to China?”

A year ago the US Senate Intelligence Committee, reviewing foreign interference in the 2016 US election, decried the fact that “Russia’s goals were to undermine public faith in the US democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency.” Yet if this sentence were amended to refer to “US goals,” “Nicaragua’s” democratic process and “Daniel Ortega,” it would precisely describe the dishonest practices that the US is following in Nicaragua, which the Sandinista government is determined to stop.

Original post: Council on Hemispheric Affairs and in Spanish here

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on